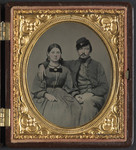

In May 1861, Charles R. Rees ran an advertisement in the Richmond Dispatch for his "finely executed" photographs and ambrotypes. In the early months of the war, scores of men traveled to the studios of photographers like Rees to have their portraits taken in their new military uniforms. Once the armies settled in camps, photographers followed to document what many initially deemed a grand adventure.

In May 1861, Charles R. Rees ran an advertisement in the Richmond Dispatch for his "finely executed" photographs and ambrotypes. In the early months of the war, scores of men traveled to the studios of photographers like Rees to have their portraits taken in their new military uniforms. Once the armies settled in camps, photographers followed to document what many initially deemed a grand adventure.

As the war progressed, photographers' lenses turned to sites of combat. Audiences, in the midst of a communication revolution, clamored for scenes of the war. A July 1862 issue of the Richmond Whig asked for "some of our photographers" to repair "to the scenes of the late battles, and take views of the fortifications, camps, etc. Such views would constitute valuable illustrations" of historical events. Taking photographs in the field proved extremely difficult. Technological limitations and cumbersome equipment made it nearly impossible to capture the action of battle; photographers instead documented battlefields after the action, landscapes, and scenes of army life. Nevertheless, the photographic achievements of the Civil War, Bob Zeller notes, "far exceeded those of any other war in the nineteenth century."

Photographers did manage to take some distant scenes of battle. In the autumn of 1863, teams of photographers recorded army and naval operations in Charleston Harbor, South Carolina. George S. Cook took two remarkable live-action shots of Union gunboats engaged in combat. Cook's two photographs were the first verifiable images of battle captured while the photographer himself was under fire. Philip Haas and Washington Peale, operating in a different area, captured five Monitor-class ironclads and the U.S.S. New Ironsides in action.

After the smoke of battle cleared, photographers traveled to the battlefields. During the course of the war, photographers recorded images of unburied dead soldiers on seven occasions—following the battles of Antietam (1862), Corinth (1862), Second Fredericksburg (1863), Gettysburg (1863), Spotsylvania (1864), and, in 1864, on the occasion of burials at Fredericksburg and Petersburg. These images, which deeply moved those who saw them, remain the most profoundly important views of the struggle. In July 1863, American poet Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. reflected on photographs from the Battle of Antietam in an Atlantic Monthly article. "Let him who wishes to know what war is look at this series of illustrations, " Holmes wrote. "These wrecks of manhood thrown together in careless heaps or ranged in ghastly rows for burial were alive but yesterday." Now, in stark black-and-white images the viewer confronted "some conception of what a repulsive, brutal, sickening, hideous thing" the war was.

Virginia played a significant role in Civil War photography. From A. J. Russell's 1863 image of Confederate officers and soldiers posed along the Rappahannock River in Fredericksburg, Virginia, to Timothy O'Sullivan's "Grant's Council of War, " taken on May 21, 1864, at the crossroads of Massaponax Church, the photographer's camera often aimed at the Virginia landscape. And, while the strains of war ravaged Southern photographic studios, the American Journal of Photography reported in September 1863, "only in Charleston and perhaps Richmond that any photographs at all are made."

While photographs captured the realities of war, photographers sometimes manipulated the scenes themselves. Historians of photography have demonstrated that Civil War–era photographers often resorted to stagecraft to convey a particular look. Alan Trachtenberg explains that photographers arranged "scenes of daily life in camp to convey a look of informality" or posed "groups of soldiers on picket duty—perhaps moving corpses into more advantageous positions for dramatic close-ups of littered battlefields." William A. Frassanito's painstaking research shows that Gardner and O'Sullivan, for example, found a youthful Confederate soldier lying dead near the southern slope of Devil's Den, near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania. After capturing several images of the youth they moved the body approximately forty yards to make the now iconic image "Home of a Rebel Sharpshooter, Gettysburg, July, 1863."

YOU MIGHT ALSO LIKE